Universal design is bad for everyone, and particularly for older adults

Universal design is the design of systems, services and products in such a manner that they can be used by the greatest extent of people, regardless of age, ability or disability.

The term ‘Universal design’ and its 7 principles were coined by Ronald Mace in the late nineties. These principles come with 30 guidelines, varying from “Make designs as simple and intuitive as possible” to “Provide adaptability to the user’s pace”. The Universal Design principles and guidelines quickly spread into the design community, and are often considered a starting point when designing systems for people with impairments… or for older adults.

I argue that starting a design from these principles and guidelines is a bad idea, particularly when designing for an ageing population.

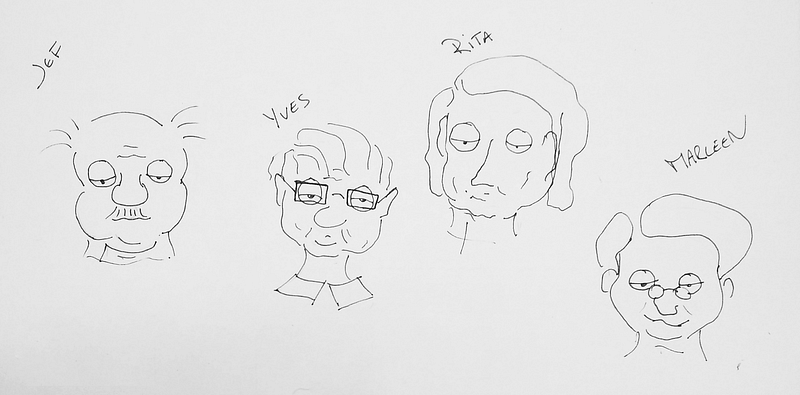

I want to start my argument by discussing the life journeys of 4 babyboomers. Let’s return to the youth of the older adults of today. We are 1950, WOII has ended and we have four 6-year-olds spending their first days in school.

If you ask Jeff for his dream, he would answer that he wants to be a soccer player. Yves, his friend, would like to become a famous soccer player too. That or a fighter pilot. If you would ask Rita, should would tell you that she would like to become a teacher. And her friend, Marlene, would like to be a teacher too, but even more, a mom of four kids. And while Jeff is the son of factory worker, and lives in a small house, and while Yves is the son of the doctor and lives is big house, they get along. Rita has 5 brothers and 1 sister at home, and her parents have a hard time making ends meet. Marleen on the other hand in an only child and spoiled by attention. Yet this does not really matter. They are best friends for ever. They are sharing the same dreams, they are sharing the same values.

Now, let us fast forward to 2016. Our 70-year olds have grown up. Let’s see what universal design tells us about these four older adults and what they need from a product.

Well, we should ensure that we “Provide adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance”. Or we should “Minimize sustained physical effort.” Or we should “Eliminate unnecessary complexity.”

According to universal design, our babyboomers are still united. This time not by their dreams and values, but by their age. And even more by their decline. Our babyboomers are in need of designs that focus on accessibility.

Defining users by their age-induced limitations is ageism. Ageism is defined as “the stereotyping and discriminating against individuals or groups on the basis of their age”. By focusing on accessibility we reduce this group of older adults to people who who are declining, who are becoming less and less able until they finally die.

Of course we can make more subtle divisions, we can talk of mediors versus seniors, and maybe discriminate between frail elderly versus active elderly. But then again we are still using one dimension to characterize our older adults, namely the extent to which they are impaired. What ever the number of divisions along this one dimension, the starting point for the design remains reductionist.

Now let’s revisit the life journeys of our elderly, according to a life span perspective. Let’s really try to grasp who Rita, Marlene, Jeff and Yves have become?

Jeff started out as a blue collar worker in the same local factory as his dad, and actually, this paid for a nice living. But when he could retire early at the age of 55, he did not hesitate. Jef never became a famous soccer player, but soccer remained his passion, and he took his role as local coach seriously. But since his retirement, he also decided to become a volunteer and teach Dutch to young immigrants. Jeff cares much about a society that is open and fair. Yves never became a soccer player either, nor a fighter pilot. He became a renowned professor in plasma physics. He even never got married but devoted his life to science and the search for the scientific truth. Marlene did become a kindergarten teacher but stopped working after her first child was born. Her 2 grand children are the lights of her life.

And Rita, started out as a housewife, but after her husband died early from long cancer, children just didn’t become part of the plan. Her nieces and nephews demand already sufficient attention. She works as a librarian, but really, the true joy in life is exploring the world. With a big group of friends she hikes all over the world. Her last trip was to the Kilimanjaro.

Heterogeneity over stereotyping

These different life journeys make that Jeff, Yves, Rita and Marlene differ much more from each other at the age of 70 than at the age of 6. Yes, some health parameters are less. Marlene now needs reading glasses. Yves actually received 2 new lenses, and can see better then ever and is still contributing to science and learning. Rita is suffering from vericose veins but that is not stopping her from training for the London marathon.

The presumption that people become more alike as they age is a common, but false presumption (Peppard 2013). As with any age group, there is great diversity among older people in physical, intellectual ability and in cultural preferences. Moreover, as people age, they become even less like their peers than younger people. As years pass, people have different life experiences, learn different things, face different challenges and respond differently to life’s events. Moreover, the actual number of years lived affects people differently as well. People age physically, emotionally and spiritually at different rates. Consequently, the longer people live, the more they differ.

Growth over decline

Research paradigms on ageing such as the Life-Span Perspective (Baltes 1987) have considered ageing to be a process of both growth and decline. While gains are particularly evident in early life and losses are more noticeable in later life, people of all ages improve skills and cognitive functioning (Freund and Baltes 2000). For example, older adults devise new strategies in one domain to compensate for losses in another (Baltes and Baltes 1990), and use media selectively to support personal growth (Van der Goot 2009). Moreover, certain older adults have a richness of experiences and an accumulated wisdom (Holliday and Chandler 1986) that is commonly ignored whereas small decreases in low level cognitive and attentional processes are enlarged. Interestingly, research show that beyond middle age, older adults actually report higher well-being.

I do not want to misunderstood. I am not arguing that older adults may not be in need of assistive technology, and or that usability does not matter. Of course this matters. Yes we should ensure that text is legible and that buttons are clickable.

I am arguing that this is not a relevant starting point for a design. What is important is to understand what is meaningful for a specific target group, realizing that “older adults” as such are not a relevant group.

So if we were to develop games for older adults, perhaps we should not start from universal design principles, but rather from what constitutes meaningful play for a specific audience of older adults.

Bob De Schutter is doing research on gerontoludology, or different player types among elderly. Guess what? Different older adults play for different reasons.